BY SOPHIE RUKIN & RIYANA SRIHARI

Disclaimer: All opinion articles posted on this website are solely the opinions of their authors, and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the National Parliamentary Debate League or its Board of Directors.

You can use this forum thread to discuss the op-ed.

Introduction

My name is Riyana, a senior at Nueva, and I’m Sophie, a junior at Horace Mann. This article is an amalgamation of the many critical debate-related conversations we’ve had over the past two weeks—reflections on Nueva SW’s lay kritik at the NPDL Tournament of Champions, our thoughts on the ideological divide between our respective coasts, and our strategy for building a stronger community.

Riyana: The first few months of my debate career were characterized by a constant sense of anticipation: I wanted to be good enough to read a kritik, or K, and finally understand the complex arguments I’d heard my older teammates talk about writing. For me, the word “kritik” encompassed a high-level set of arguments that fostered inclusivity and nuanced discussion of critical literature. Yet for Sophie, the word “kritik” represented a high-level set of arguments that excluded non-technical debaters and hindered deep discussion of policy.

Sophie: I learned about Ks in waves. The first time the word was mentioned was my freshman year, when I received the fastest run-through of tech debate known to man. The seniors teaching me were cool and experienced, and I listened carefully, hoping to absorb everything they said. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a room full of more disgusted faces and sounds than when someone brought up Ks, which were explained to us as awful arguments that we didn’t have to worry about on the East Coast. I didn’t know what Ks were leaving that meeting, but I knew I hated them. “Kritik” became a buzzword. It didn’t have to mean anything for me to know that they were the antithesis of everything I loved in debate.

A Brief History of the Kritik Controversy

Truthfully, kritiks aren’t unilaterally inclusive, nor are they weapons for evil. In the end, they’re just another argument—and, like all arguments, they can be used for positive and negative ends.

Kritikal debate originated in the 1980s and was popularized as a survival strategy for Black debaters in the 1990s, who used the K to resist structural oppression in the debate space. Now, the K continues to be a tool for marginalized debaters who resist harmful resolutions and practices within the debate community. Yet, as kritikal debate entered the mainstream parliamentary zeitgeist (and newer, more esoteric forms of kritiks became popular), kritiks became contentious arguments that inspired ideological resistance.

While exploring neoliberalism and patriarchy (or more obscure concepts like hyperreality and aesthetics) is important to kritikal debaters who strive to critique the entrenchment of politics in systems of oppression, many view these kinds of kritikal arguments as exclusive, or think that kritiks are distractions from the purpose of our activity. But looking beyond this ideological divide, much of the current kritik-related animosity is the product of past practices. From 2016 to 2020, tech teams employed strategies of “spreading out” less-experienced debaters: reading complex tech positions quickly and refusing to take POIs or slow down when asked. While this strategy has fallen out of favor, and tech judges’ norms have changed to intervene against this behavior, we still feel the residual impacts of this disturbing trend.

At the same time, the kritik has historically been useful for increasing access to debate and spotlighting issues of debate-specific inequality—so when a team reads a kritik at a reasonable pace, takes POIs, and carefully explains confusing jargon, the response that the K is “inaccessible” only prevents critical literature from having an impact on our community, and stops debaters from expressing the arguments they love in inclusive ways.

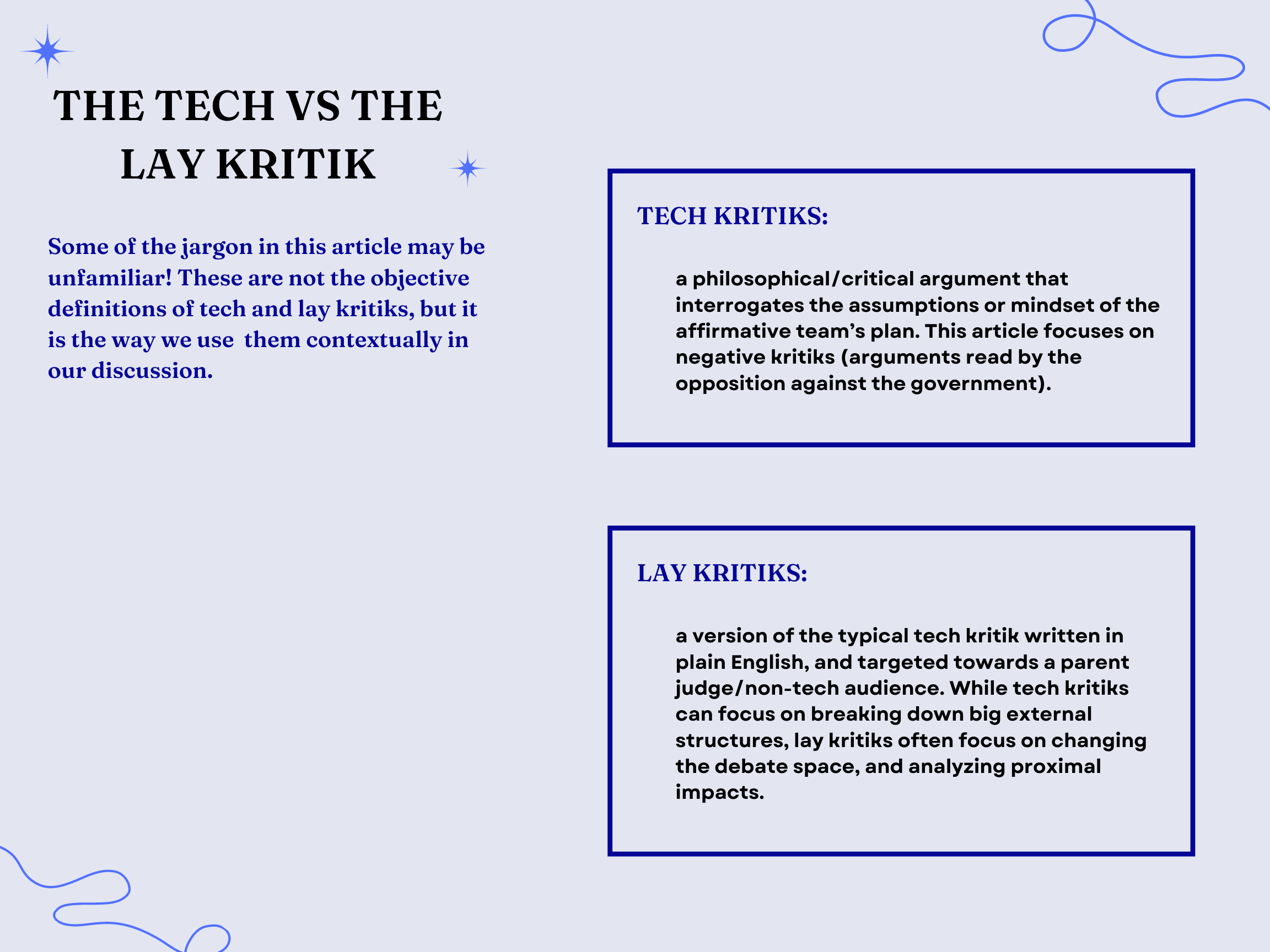

Graphic by Esha Shah

The Lay Kritik

Riyana: My partner Abi and I have been running our material feminist kritik, which interrogates the intersection between patriarchy, capitalism and imperialism, real-world organizing, and debate, since junior year. The kritik was our project; we hoped to break through anti-k and misogynistic ideology in the debate space and normalize critical discussion of structural patriarchy. Consequently, an important goal of that project was to expand it beyond an audience already receptive to critical literature. Inspired by Renée Diop and Rhea Jain’s incredible kritik on anti-Blackness and assimilation that won the CHSSA State Championship last year and Ryan Wash and Elijah Smith’s groundbreaking kritik on the search for home, Abi and I wrote a lay version of our argument, or a more simplified form of the kritik, created for non-tech judges and debaters. Through reading our feminist theory at TOC, we hoped to expose how patriarchy pushes gender minorities out of debate, combat complacency towards these experiences, and outline a survival strategy to resist these harms. We read our position five times in front of a varied group of judges and debaters at the NPDL’s Tournament of Champions, and Sophie witnessed our quarters and semis K rounds.

Sophie: The lay K was incredible. Two extraordinarily talented female-identifying debaters got up and read a K that they resonated with, and they didn’t do it to win. Neither their quarters nor their semis panel were “West Coast tech,” and it was the final tournament of their career. Still, Riyana and Abi risked it all to run something they cared about. I was nervous when I joined the quarters zoom and heard discussion about a K. The constant horror stories of K debate replayed in my head. But when the K started, it was slow, I could understand it, and I could even flow it. They took every POI, promoted a message that really made me smile, and I knew this was not the K I had heard about in lectures.

Riyana: In the past few weeks, I’ve had some incredible conversations with Sophie about what an ideal kritik round looks like, and Sophie has all kinds of brilliant ideas about how she would respond to our K—such as by challenging our alternative or reading disadvantages to our activist strategy. The best kritik rounds are the hardest ones, where debaters are truly engaging with your argument and defending their own position in good faith. That was what we hoped for at the Tournament of Champions. However, in many of our rounds at TOC, we encountered a lack of engagement with the kritik, and some of our opponents would not discuss the issues we raised unless we conceded the round.

Sophie: I empathize with this response. Ks are scary when you aren’t used to them, and having a conversation (instead of a K round) is probably much more in all of us lay debaters’ comfort zones. However, a debate round is an opportunity to learn and grow, and at face value, a request to have a discussion is a request to stop debating entirely and do something else. As debaters, we show each other respect by responding to each other’s claims, and we can’t have productive conversations by simply refusing to listen to each other. Beyond this, while discourse is good, and having a conversation about misogyny is excellent, Riyana and Abi tell you themselves in the K why discourse doesn’t do enough. Stopping debate rounds to have discussions can be valuable, but when someone explains to us why discourse doesn’t do enough, we have an obligation to listen, even if we disagree. Tying their advocacy to a ballot asks people to look at politics and debate topics through a critical feminist lens, and I wish teams had engaged with that claim more substantially. You don’t have to agree with something to learn from it.

Riyana: The other common TOC response to the K was some form of anti-K theory.

Sophie: I understand why teams opt for this strategy, and theory can often be a good approach when hitting abusive kritiks. But the core argument of that kind of anti-K theory shell is that the K is impossible for teams to understand—and to the point where East Coasters run frameworks on everything from Buddhism to anthropocentrism, I couldn’t understand why this K was uniquely harder to respond to than complex East Coast arguments. I have seen inaccessible Ks before, and this was not one; as an East Coaster with very marginal K knowledge myself, I understood it. It is vital that we recognize nuances within Ks and how they are read. Riyana and Abi chose to make the round ultra-accessible. The community should applaud that.

Riyana: Fundamentally, a refusal to engage with the substance of the debate echoes the “I don't think this has anything to do with us” rhetoric that we critique on the impact section of our K.

Sophie: Perhaps the worst part of this strategy is how much it hurts the debaters who read it. Students who are only taught anti-k ideology become convinced that they can’t properly respond to the kritik. Some of the best debaters we know refused to engage with Riyana and Abi’s K, not because they couldn’t, but because they had been told that they couldn’t—and the system of debate that makes incredible thinkers believe they are incapable is largely to blame for the refusal to engage in kritikal advocacies.

The Reactions

In response to the kritik, some debaters argued that the structure was inaccessible; that even if the arguments were true, the format of the K inherently excluded non-tech teams. Others argued that the issue was overblown, or that misogyny in debate was already recognized, and didn’t need to be amplified in elimination rounds. But what stands out to us amongst almost all of these perspectives was that a majority of the arguments against the K had nothing to do with the kritikal advocacy, and everything to do with the format it was read in. The constant litigation of the way debaters are allowed to read arguments about our experiences—including attempts to require us to end our competitive careers—is an effective refusal to engage with real issues of misogyny in debate.

Riyana: With the usual anti-k talking points around exclusion or complexity off the table, the biggest negative response to the lay kritik was criticism of the validity of specific warrants in the K. To be clear, every source in the kritik has been cited, and these issues have been well-documented. But even looking beyond the specifics, the implication of this kind of opposition to the kritik is horrifying. Opposing the kritik by aggressively fact-checking the warrants ignores the core claim of the K: that debate can be a misogynistic and toxic space, and that perpetrators of this abuse are aided and abetted by those in power. The thing that frightens us most about debate, kritikal or not, is the possibility that someone's desire to win will supercede their desire to act ethically—both in terms of the arguments they make, and the way that they make them. In this case, it feels like the desire to prove that kritiks are unilaterally bad has superseded the obligation to protect the community from misogyny.

Sophie: I understand why people feel averse to the structure of the K, because I shared the anti-k sentiment for a long time, too. However, attending the Berkeley Invitational, where I met a tech debater who generously taught me everything I know about critical debate, and discussing kritikal debate with Riyana and other West Coast friends has altered my perspective. While I’m still not a K debater and would likely never run one myself, the arguments they bring up are important and necessary to listen to. Opinions can change—and while I’m not asking you to change yours, I think there could have been a lot of value in just considering Riyana and Abi’s.

Riyana: However, while we’ve received some negative feedback, we’ve also received some incredibly positive reactions to the kritik. From Sophie’s post-Quarters Zoom message to another debater’s post-tournament Instagram DM, we’ve been lucky enough to connect with peers and begin the process of building solidarity in the exact way we outlined in our kritik’s alternative. Some of our favorite RFDs came from judges who shared their own experiences of misogyny from their time as debaters and said that they felt heard and represented through our kritik. This kind of positive feedback from debaters and judges who were complete strangers (or not particularly receptive) to Ks has allowed us to see the tangible impacts of the lay kritik. Most importantly, it has given us hope for our younger debaters, who will hopefully be able to be part of a stronger and more equitable parliamentary debate community next year.

Our Reflections

Riyana: These conversations brought us to a larger question: what should the role of the kritik in high school parliamentary debate be? There are issues of inequity that seem almost endemic to the debate space; Abi and I wrote our kritik in response to the lack of effective strategies for combating deeply-rooted misogyny in the debate space. At the same time, different norms on argumentation, tournament structure, and out-of-round equity practices create very different conditions for the utility of the K in solving these issues.

Sophie: East Coast tournaments have hour-long equity briefings before every tournament and monthly board meetings to discuss league-wide equity policy, and this gives East Coast debaters more agency to shape the debate space for themselves outside the round. With that being said, equity cannot solve everything. It can’t erase offhand sexist comments in team rooms or gendered slurs from opponents. Equity projects deal with the interpersonal, and while they can try to create sweeping change, it is hard to alter entrenched views with league policy. So, while I don’t necessarily think the East Coast should incorporate the use of Ks into our style of debate, I understand where the desire to do so comes from. The differing norms of East and West Coast resolutions may also explain this anti-K ideology on the East Coast. When I think about my favorite East Coast topics, my receptiveness to K arguments makes sense; debating feminist theory or running marginalized groups framework allows me to have conversations about a lot of the same topics that K debaters try to discuss.

Riyana: When debaters get rounds in tournaments on whether or not “This House supports violent revolution against political oppression” or “This House regrets identity politics”, perhaps their desire to engage in critical discussion is satiated through a venue that West Coasters generally lack access to. Even so, one of my favorite aspects of kritikal debate is that it allows me to escape the switch-side limitations that make people argue that capitalism is positive for feminist movements in one round, then argue that feminist liberation is made impossible under capitalism in the next. Ideological consistency and an ability to avoid arguing for a side that feels morally reprehensible are the things that draw me to kritiks, and provide me the agency that simply debating the topic does not.

With that being said, the goal of this article is not to pinpoint the exact reason that debaters on both sides feel such animosity over the kritik, but to examine how we can build a community that embraces equitable discussion of a range of issues. Our primary goal is not to change deeply-rooted opinions on kritikal debate, but to share the things we’ve learned from each other and forge a new kind of discourse around the East-West divide—one that acknowledges the humanity of both sides, and prioritizes the most educational, empathetic, and inclusive form of debate possible.

While debate is meant to be a place for disagreement and productive discourse, a community cannot subsist on a biannual fight at the NPDL Meeting of Members. We have an obligation to respect each other’s pedagogy and remain curious and kind—but this work is only possible if we listen to and communicate with each other. Trust us, even a simple Zoom DM can create a lot of change.

Further resources on kritiks/framework debate

Introduction to Kritikal Debate Slides by Pascal Descollonges

The Parli Prepbook - Kritikal Debate Excerpt by Kyle Dennis et al.

Kritik Structure Lecture Outline and Supplemental Videos by Trevor Greenan

The Kritik-Focus Model of Debate by Elijah Smith

Framework Theory (No Aff Ks) by Nueva Parli